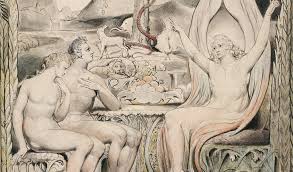

When John Milton published Paradise Lost in 1667, there were many who were unhappy with his work. The poem was not simply a reiteration of Milton’s strong republican ideas, support of Cromwell, and apology for the regicide, it was a substantive piece of art that discussed the fall of man with characters of fervent human emotions.

Paradise is a place of peace, of gardens, of man’s husbandry of the land, of his unique relationship with animals, of innocent nudity, of cooperation between husband and wife.

Yet when Milton introduces Satan as he wakes in a fiery Hell after the Fall, Satan looks at his new abode and says: “…Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven . . .” Those dissatisfied with the work believed that Milton had given to an evil Satan attributes that made him the most interesting character of the story.

Yet when Milton introduces Satan as he wakes in a fiery Hell after the Fall, Satan looks at his new abode and says: “…Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven . . .” Those dissatisfied with the work believed that Milton had given to an evil Satan attributes that made him the most interesting character of the story.

Perhaps the end of an era of hitchhiking was much the same—the introduction of uncertainty, danger, and political and personal selfishness into an innocent world. Was it only our tasting of the forbidden fruit of freedom and experience that opened our eyes to danger? Had evil been there all along? Or had the world actually changed for the worse?

The decline of hitching began in the eighties, the years of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, with harsh government attitudes toward counterculture ideas, with the elevation of capitalism to the status of a religion, and to the push for consumerism to “promote the economy” as the patriotic duty of each citizen.

In an article in The New York Times (November 10, 2012), “Hitchhiking’s Time Has Come Again”, Ginger Strandnov writes:

“…it was the ’60s and ’70s counterculture that embraced hitching as an anti-consumerist, pro-environment celebration of human interdependence. Students were hitchhiking to antiwar demonstrations. Civil rights advocates thumbed rides to register voters in the South. The American automotive industry, by then, had gone into overdrive: there were more cars than ever on the road. Yet an entire generation of young people, it seemed, was on the move without buying them.”

Not only were the longhairs regarded as parasites on society, as expressed by their bumming rides off of others, but also often they were people who were ‘unproductive’, taking time to see vistas or the land, enjoy trees, flowers, and wildlife.

“I remember nearly every ride, and with fondness, that I have taken. Its not just the rides either, its walking down long deserted highways among nature and beautiful scenery, while everyone in their buses zoom by not seeing a thing (Justin Karmak, True Nomads, ‘Four Reasons Why You Should Hitchhike’, March 24, 2013).”

In contrast, as early as 1966, Ronald Reagan was already battling conservationists in favor of industry:

“I think, too, that we’ve got to recognize that where the preservation of a natural resource like the redwoods is concerned, that there is a common sense limit. I mean, if you’ve looked at a hundred thousand acres or so of trees — you know, a tree is a tree, how many more do you need to look at?”

By the eighties, there was an enormous extension of car ownership, the completion of major freeways and interstates with more difficult access to roads, and drop offs by drivers into “black holes”, places from where it was difficult to get a ride.

By the eighties, there was an enormous extension of car ownership, the completion of major freeways and interstates with more difficult access to roads, and drop offs by drivers into “black holes”, places from where it was difficult to get a ride.

In addition to pubic attitude, the physical dynamics of changing roadways, and the proliferation of cars, there was also the very real danger of predators on the roadways.

“In the summer of 1964, Berkeley student Jo Freeman, veteran of the Bay Area civil rights movement, hitchhiked across America. Her destination was the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City where the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was challenging the segregationists for control of the Mississippi Democratic Party (At Berkeley in the ’60’s, December 24, 2003).”

Jo writes: “Saying NO early and often was generally my best defense. I was often surprised at some of the men who thought a girl in his car was sexually available. In the midwest I was picked up by a fortyish man who said he had just dropped his daughter off at college, and I reminded him of her. Ten minutes later he asked if I would go to a motel with him. By the end of my trip I had learned that it was neither provocative dress nor physical attractiveness that turned a female into potential prey; it was vulnerability.”

Changing international political climates, also changed the face of feasibility. In the late sixties, I had friends who took the Icelandic Airlines route (along with thousands of others) to Reykjavík, then began the long hitching road to India. One family I knew hitched to India with a two-year-old. A glance at the “Hippie Trail” of the sixties and seventies below, is enough to explain why hitching today in these parts of the world would be challenging.

By the late-seventies, many of those of us who had been hitchers during the sixties knew personal stories of abuse and violence. Burned, we not only gave up hitching, but could no longer afford the risk of picking up hitchhikers. The world had turned unsafe in many ways—we picked our children up at school, went with them into public restrooms, made sure we had close hold in a crowd. And unlike the entry of Satan into Paradise, none of us found evil interesting.

Remarkably, hitching may once again be on the rise. Sites like http://hitching.it allow hitchers to exchange knowledge about the best places to thumb a lift. Countries like Nepal, Cuba, Israel, Poland, and the Netherlands are encouraging and promoting hitching. Sometimes the issue is one of few cars in an area, other times the high cost of fuel, and at others, a desire to leave the least amount of carbon footprint.

Designated hitching area in the Netherlands

Those of us who were avid hitchers in the sixties are left with memories of a gentler time, one of laughs along the road, adventure, and new friendships. We have an eye turned to see what the future will hold, a future that still needs to be shaped by our actions.

“In a society where everything has a price,” Joe Moran writes, “it becomes harder to sustain what the social policy expert Richard Titmuss called the gift relationship: the kinds of exchanges based on trust and goodwill that bring intangible benefits to everyone but are the hardest to retrieve when they are gone (The Guardian, “A Guide to Hitchhiking’s Decline”, 2009).